Sutro Library Manuscript

Thanks to the kind help of Diana J. Kohnke, librarian of the California State Library, SFSU, Alberto Mesirca recorded for the first time the wonderful original 19th Century compositions for solo Guitar taken from the Mexican manuscripts (SMMS M2 and M5) of the Sutro Collection, a branch of the California State Library.

Tracks

01. Zapateado N. 1

02. Zapateado N. 2

03. Zapateado N. 3

04. Zapateado N. 4

05. Sonatina N. 1

06. Sonatina N. 2

07. Sonatina N. 3

08. Sonatina N. 4

09. Sonatina N. 5

10. Sonatina N. 6

11. Tema con variaziones N. 1

12. Tema con variaziones N. 2

13. Tema con variaziones N. 3

14. Tema con variaziones N. 4

15. Tema con variaziones N. 5

16. Tema con variaziones N. 6

17. Polacca N. 1

18. Polacca N. 2

19. Minuetto afandangado

20. Vals

21. Allegretto

22. L’italiana in Algeri

23. Jarave

*

*

New sources of music from Spain and colonial Mexico at the Sutro Library

an article by John Koegel, dated 1999,an exhaustive description of the contents of the manuscripts

The printed and manuscript Mexican materials now in the Sutro Library were purchased by the wealthy San Francisco book collector Adolph Sutro (1830-1898) from the important Mexico City bookseller and publisher Francisco Abadiano and his son Eufemio in 1885 and 18897 Adolph Sutro, born in Alsace, arrived in San Francisco in 1850 at the height of the Gold Rush and established a lucrative career as a cigar importer. Great wealth came to him when he successfully planned and engineered the Sutro Tunnel to drain the Comstock Lode silver mine in Nevada, which at the time was flooded by water and generally inoperative. Influenced by social movements of the era, Sutro became a philanthropist: he built the Sutro Baths (a huge indoor swimming pool) and the famous Cliff House in San Francisco, created the Sutro Forest on San Francisco’s highest hill, served as mayor from 1895 to 1896, and laid plans to establish a public library in the city. With the future library in mind, Sutro became a large-scale collector of manuscripts, rare books, and other materials, using the services of agents to buy entire collections in Europe and elsewhere. Before long, his collection included Hebrew, Egyptian, and medieval European manuscripts, and first editions of Shakespeare. To escape an understandably irate wife who had just found out about the mistress he had hidden away in Sutro, Nevada (the town he established near the entrance to the Sutro Tunnel, near Virginia City), Sutro traveled by train from San Francisco to Mexico City, where he encountered Francisco Abadiano’s bookstore, one of the city’s leading bookshops, which contained an eclectic array of manuscript and printed items. Some of Abadiano’s stock derived originally from the Zuniga y Ontiveros and Valdes families, important early Mexican printers and booksellers. Abadiano was related to these families through lateral familial and commercial ties. Another portion of Abadiano’s stock came from the libraries of religious colleges, convents, monasteries, and churches that had been disestablished as a result of President Juarez’s reform legislation. Part of Abadiano’s purpose in holding on to this large and disparate collection of materials (at the time not thought generally marketable) must have been to preserve this portion of Mexico’s historical patrimony. Intrigued by Abadiano’s collection, Sutro bought the entire contents of the bookstore. According to W. Michael Mathes, honorary curator of the Sutro Mexican Collection, Abadiano apparently crated up the contents of his shop and shipped them to Sutro in San Francisco.

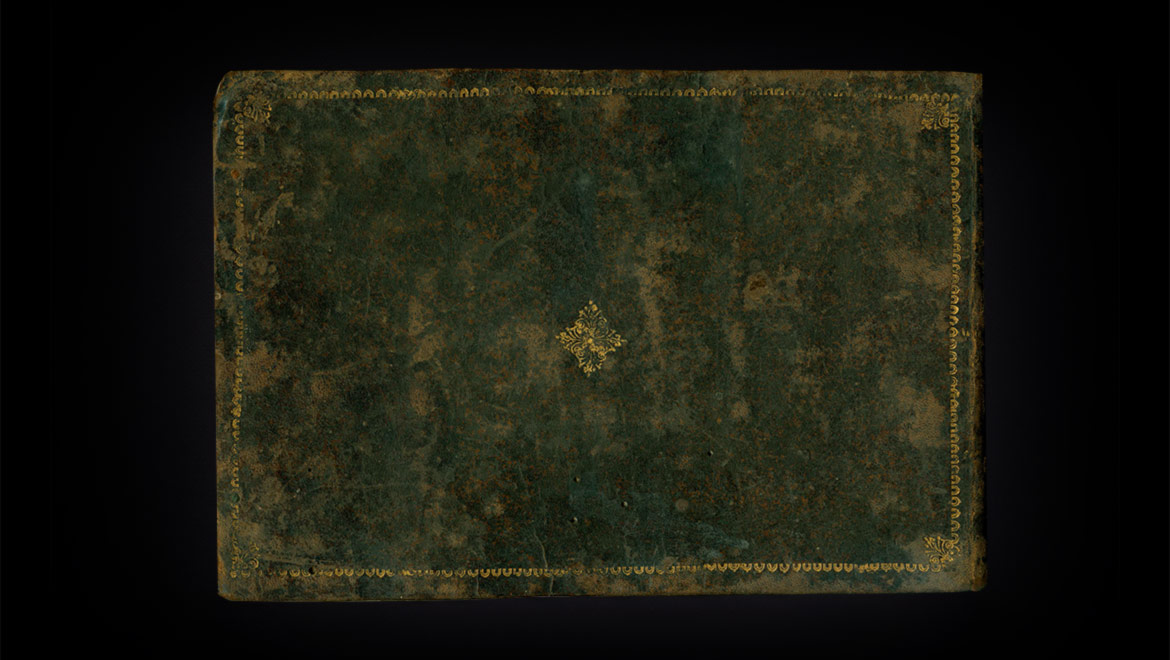

[…]Sutro Library manuscript SMMS M2, labeled “Coleccion de piezas de musica escogidas a dos guitarras,” is probably the most musically significant of the three Mexican collections discussed here. Dating from the 1820s or later, this collection of arrangements for one or two seven-string guitars contains a mix of Mexican, Spanish, Italian, and other European genres. Significantly, the collection ends with a Mexican jarabe that includes precise tuning indications for the seven-string guitar. The music notation, however, is not as precise or complete for this jarabe; rather, it gives an initial melodic and rhythmic model followed by improvisational models.The virtuosic arrangements for two guitars of the overtures to Rossini’s operas Tancredi, L’italiana in Algeri, and Il barbiere di Siviglia contained in SMMS M2 document the importance and general public acceptance of Italian opera in Mexico beginning in the 1820s. The staged performance in Mexico City of Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia presented by Andres del Castillo in Spanish translation in 1826, and the performances of Italian operas given in 1827 by Spaniard Manuel Garcia and his company (first in Italian, then because of public demand, in Spanish translation) signal the beginning of the importance of Italian opera in Mexico in the nineteenth century. These guitar arrangements are an indication of this growing influence. SMMS M2 also includes four rondos, two minuets, two waltzes, a bayle ingles, the overture and “Aria de Colas” from El tio y la tia (1767) by Spaniard Antonio Rosales, an “Adagio de Haydn,” and four theme-and-variation sets, including one by Manuel Antonio del Corral (b. 1790). (Corral’s “Variaciones” include a final variation interestingly marked “rondo.”) The French invasion of Spain forced Corral to flee to Mexico to escape the consequences of composing the anti-French theater piece El saqueo, o Los franceses en Espana (ca. 1808). Although a Spaniard, Corral was influential in the musical life of Mexico City. As Ricardo Miranda points out in his important study of Corral and his edition of Corral’s Variations, as a foreigner in Mexico (a gachupin, or Spaniard), and a staunch monarchist at that, Corral was the wrong man at the wrong time in the wrong place.

[…]Sutro Library manuscript SMMS M5 contains eighty-three unattributed works arranged for guitar and bass instrument (perhaps a second guitar or harp, although without any figures indicated). Most are dance forms, including sets of fourteen contradanzas, seven waltzes, six zapateados, two boleras , two polacas, two alemandas, twelve minuets, a minuet afandangado, and a bayle ynglesito. Others are artmusic forms, including sets of six rondos, six sonatinas, six pastorelas, and six theme-and-variation sets. The rondos and pastorelas may have also been used in a dance or theatrical context. The manuscript is beautifully copied and possibly represents a large portion of a professional or advanced amateur musician’s working repertory.

As with some other manuscript collections of secular music from colonial Mexico, the compiler’s name and the sources of the music are not given in SMMS M5. Certain other manuscripts from the period, however, do give the names of their owners and compilers, as appropriate, along with the date and location of ownership. A good example of this is the Eleanor Hague manuscript from the Southwest Museum in Los Angeles, California, which contains dance music for violin along with important choreographic information. Owned in 1772 by Joseph Maria Garcia in Chalco (a town close to the capital), it was bought in 1790 by Joseph Mateo Gonzalez Mexia for two pesos after Garcia’s death. Craig Russell has pointed out the many French and English sources of the fiddletunes played in late-colonial Mexico preserved in the Hague manuscript.

Though no date of compilation or composition is indicated anywhere in SMMS M5, the inclusion of the six waltzes in the manuscript leads me to believe that it dates from the first few decades of the nineteenth century, the probable time of the introduction of the waltz into Mexico. After the turn of the century, the Holy Office received complaints about the lasciviously close physical proximity of the partners during the dance. I wonder, therefore, if SMMS M5 might not date from the second or third decade of the nineteenth century, after the storm of ecclesiastical opposition to the waltz had abated.

This manuscript collection presents an interesting mix of Spanish and other European music – particularly for the dance – but, significantly, no examples of local Mexican dance music. This leads me to conclude that the manuscript may have been imported from Spain. Since a great deal of printed music was imported to Mexico from Europe through Spain and sold by book dealers, it is almost certain that manuscript music was also imported and sold on a grand scale. The Spanish pieces represented in SMMS M5 – the zapateados, boleras, polacas, and the minuet afandangado – enjoyed a long popularity in Mexico well after their original introduction in Spain. This collection is important also in that the several notated variations that follow each of the six individual zapateados indicate how this instrumental dance form could have been improvised in live performance. I believe that these variations provide stylized models for possible forms of improvisation.